Part 1:: Thinking about STEEP forces in a sustainable city (practice)

In-class activity Masdar 2050 futures scenario activity (watch 15 minutes of the video below)

Link to list of other documentaries you can watch on Masdar City.

Think about the type of future that is depicted in the video. Ask yourself what are the challenges you imagine with Masdar? What would be challenging about living in Masdar?

Masdar design activity: You’ve just seen the SHELL documentary on the Masdar pilot city. Imagine that Masdar wants to grow to accommodate 3 million people. (a) Critically analyze what you just saw in Masdar according to the STEEP forces (Social, Technological, Economic, Ecological, Political).

STEP 0: Work on a team. Click “Make a copy” under “File” the Google slide linked here, and rename the file. Share the link to the copy you just made with your team members so you can all work in the same slide deck.

(15 minutes) STEP (1)

Discuss and fill out what might be some pros and cons of Masdar from a STEEP perspective? Fill in the table.

(15 minutes) STEP (2)

Identify one aspect, problem, opportunity, or issue that is of interest to you to explore further through the lens design. What aspect of the current Masdar pilot do you think would have difficulty scaling to 3 million people?

(15 minutes) STEP (3)

Sketch a problem storyboard for what a day in the life experience might be like in Masdar with the problem or issue you identified. Provide captions for each frame.

(10 minutes) STEP (4)

Provide a solution storyboard of what the improved experience you identified above might be like in Masdar. In short, what would a day-in-a-life look like if the problem you identified were solved. Provide captions for each frame.

(10 minutes) pm STEP (5)

Brainstorm five new concepts for products (or designed experiences) to resolve the problems you identified in your storyboard above. Provide a drawing and description of each concept.

Part 2:: Critiquing Visions of the Future (theory)

Watch the following video by Futurist Jamais Cascio.

Q. When constructing futures scenarios, what are the pitfalls that Cascio warns us to avoid?

Futurist Jamais Cascio on “Bad Futurism”.

Answer the following questions as you watch the video. Multiple choice discussion questions link.

Group discussion questions.

1. According to Cascio, what matters most when constructing futures scenarios?

2. According to Cascio, does everything usually work as expected in believable futures scenarios?

3. According to Jamais Cascio, should scenario designers focus on a narrow demographics in futures scenarios?

4. What role do “brands/product placement” play in futures scenarios?

5. What kind of human behaviors in the future is likely to reflect believable human experiences?

6. What kind of alternative scenarios are reasonable to develop?

7. What kind of relationship should a scenario writer seek to establish with his/her audience?

Bringing it back to design

Jamais Cascio makes three main critiques of futures scenarios that:

- (a) focus only on technological advances, and miss how people live;

- (b) assume everything works, and miss the failures and the unintended uses of technology;

- (c) focus only on the access of technology by the dominant class, and don’t consider the broader impact on society.

Next you will critique your Masdar exercises through Cascio’s critiques.

How might you incorporate Cascio’s three critiques into your design practice?

Part 3 :: Critiquing another teams project with Cascio’s critiques (practice)

A reminder of Jamais Cascio’s critiques…

- Limitations of scenarios that (a) focus only on technological advances and missing how people live; (b) ignore unintended uses; and (c) focus only on the dominant class missing the broader impact on all of society.

- The second flaw involves ignoring human nature in futures scenarios.

- The third flaw, entails lacking respect for the intelligence of the audience (e.g., make your case and trust your audience to choose the better scenario; provide equally seductive and terrifying scenarios that prepare for success and failure).

Break up the teams into halves (sub group a, subgroup b). Have subgroup (a) from one team meet with subgroup (a) from another team. Subgroup (b) from the team meet with another subgroup (b) from a different team.

Half of the each team meets up with a half of another team. You will provide each other with feedback based on Jamais Cascio’s critiques of future scenarios. Make a copy and rename this slide deck link to capture the discussion / feedback session.

Do Step 7 on the slides. Answer questions 1-6 for each team’s project.

When you’ve answered questions 1-6 for both teams, each subgroup should go back to their original teams to discuss and integrate what they heard in the feedback session.

Work on Step 8 together as a team.

Step 8. Based on the feedback, what changes should you make to your concept?

Based on the Cascio Style critiques of your Masdar scenario, what changes would you have to make to your storyboard and Masdar design concepts address such critiques? Why do you think your proposed changes address Cascio’s critiques?

Step 9. Re-sketch your concept storyboard for what a day in the life experience might be like in Masdar that takes into consideration the Cascio critiques. Provide captions for each frame.

Step 10. Revise your product concept

Modify your Masdar product or experience concepts to accommodate the storyboard in step 9. Provide a drawing and description of the concept.

Part 4 :: Jim Dator: Caring for Future Generations (theory)

Why should designers concern themselves with futures studies? How might futures studies provide designers with new perspectives that drive innovation? In this page, we explore two big ideas put forth by Jim Dator: what are our obligations to future generations; and, what is, and is not part of futures studies.

First, as we all know the world is full of designed things and as designers we need to think beyond making something to consider the product lifecycle and implications of what we design. It is common for designers to think about how does what we design affect the end-user. Some of the largest failings of human-centered design are to ignore how design affects the workers manufacturing a product, the communities, the environment, other life forms on the planet, and so forth. In the first reading, Jim Dator asks you to think about how what you do (or choose not to do) might affect future generations.

Caring for Future Generations Jim Dator July 2007

Present generations must learn to care and to be concerned about not only themselves, and their ancestors, but also unborn generations yet to come. How did this unique obligation of present generations to future generations come about, and how might this obligation become more widely recognized, and fulfilled?

For tens of thousands of years, humans lived in environments of almost no novelty. For them, everything was as it had always been before. Scarcely anything was novel. For eons, humans lived in societies where roughly 80% of the future was exactly the same as the past, 15% of the future operated on some cyclical basis, and at best only 5% of the future was new and unprecedented.

We are biologically and psychologically conditioned to live in such a predictable, precedent-governed world, I believe. Each of us is most comfortable in believing that our future and that of our children and grandchildren and beyond will be basically like our present, just a little better, we hope, but not significantly different. “A sigh is just a sigh,” we sing. “The fundamental things persist as time goes by.”

Well, that is not the case. We now live in a world of perpetual change and novelty–where that which is unprecedented overwhelms whatever continuity from the past might linger on.

In the past, the best we could expect to do for our children was to pass on to them the wisdom of our ancestors just as we had received it from our parents and they from their parents before them.

Then, a few hundred years ago, and especially within the last fifty years, a new perspective has come to dominate the world – the idea of progress, development, and economic growth. The belief propelling “progress” was that, by engaging in a certain kind of economic development, and all the social change that went with it, we could pass on to our descendants something even better than that which our ancestors gave us – we could give our descendants the key to endless economic growth and ever-increasing wealth and opportunities.

That belief in “progress” is still firmly in the driver’s seat everywhere in the world. All governments are still racing towards this future. But more and more voices and forces worldwide also are questioning the idea and institutions of “development” wondering whether we are not, in fact, giving our children a worse world compared to the one we inherited from our ancestors more crowded, more polluted, more indebted, more unstable, more dangerous, more unfair, more artificial and for which the wisdom of our ancestors is less and less relevant, even though we teach and preach the old ways with more vigor and insistence than ever.

Whatever the truth of the matter here, we are for the first time faced with a new ethical question for which neither the wisdom of our ancestors nor the advocates of continual progress have a satisfying answer. And that ethical question is: “What are the obligations of present generations towards future generations?”

By “future generations” we do not mean our own children and grandchildren. That is far too easy. Of course we care about them! (Or do we? Look at the abused and neglected children all around us now!)

By “future generations” we mean all future life, everywhere, and forever–from here to eternity. And not just human life, but all future life of all kinds.

How can we in the present accurately identify the needs of future generations? Can we be sure that by satisfying ourselves we are also satisfying the needs of future generations, or at least not preventing them from satisfying their needs for themselves?

And, if we can somehow identify the needs of future generations, how can we then act ethically and responsibly in the present to enable future generations to satisfy their needs?

These are new ethical problems about which all previous philosophical, ethical, and spiritual traditions are essentially silent. Neither Jesus, nor the Buddha, nor Confucius, nor Mohammed, nor Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, nor St. Augustine, nor even St. Thomas Aquinas, or any of the others has written clearly and distinctly about your obligation towards future generations, although you might find useful hints and phrases in their sayings and actions.

Can we rise above our selfish focus on ourselves and our narrow present strip of time, and find a way to include the needs of future generations in our present-day decision making? It is a unique challenge, and ours is a unique responsibility.

There have been several important actions taken recently. Unesco, a unit within the United Nations, passed a “Declaration of the responsibilities of present generations towards future generations” which is certainly a major step in the right direction. And the Supreme Court of the Philippines has held that certain people speaking on behalf of future generations have legal standing in court.

But we need much more than that. We need your commitment.

Future generations–they are our conscience. We must think and act for them, as well as for our own interests.

Jim Dator: What future studies is and is not

Jim Dator explains what futures studies is, and is not. He provides three laws to help you remember the main ideas. From a design perspective, it is important to distinguish entertaining stories about the future and critically interpret and use ideas from the field of futures studies.

Dator, Jim. (2019). What Futures Studies Is, and Is Not. 10.1007/978-3-030-17387-6_1. http://www.futures.hawaii.edu/publications/futures-studies/WhatFSis1995.pdf

- WHAT FUTURES STUDIES IS, AND IS NOT

- Jim Dator

- http://www.futures.hawaii.edu

Futures Studies is generally misunderstood from two perspectives. On the one hand, there are those who believe it is, or pretends to be, a predictive science which, if properly applied, strives to foretell with reasonable accuracy what THE future WILL BE.

There is no such futures studies worthy of your attention. Nothing in society beyond the most trivial can be precisely predicted. Whatever might have been thought to be the case in the 19th and early 20th Centuries, we should all know by now that society is not some gigantic machine, the future states of which, if its inner workings are properly understood and its operations carefully calculated, can be precisely pre-determined.

On the other hand, it is not the case that it is hopeless to try to anticipate things to come, or that anyone’s guess is as good as anyone else’s. Even though the future cannot be predicted (and certainly no prediction of the future, no matter how eminent the source, should be uncritically “believed”), there are theories and methods that futurists have developed, tested, and applied in recent years which have proven useful, and Exciting.

Understanding and applying the theories and methods of futures studies will enable individuals and groups to anticipate the futures more usefully, and to shape it appreciably more to their own preferences.

Over the forty years that I have been teaching futures studies and doing futures research, I have come to understand that there are two basic things to understand about the future, and hence about futures studies. I have, somewhat jokingly, framed them as “Dator’s Laws of the Future.” They, and a few of their corollaries, are stated here in capsule form:

I. “The future” cannot be “predicted” because “the future” does not exist.

Futures studies does not–or should not–pretend to predict “the future.” It studies ideas about the future–what I usually call “images of the future”–which each individual (and group) has (often holding several conflicting images at one time). These images often serve as the basis for actions in the present. Individual and group images of the futures are often highly volatile, changing according to changing events or perceptions. They often change over one’s life. Different groups often have very differing images of the future. Men’s images may differ from women’s. Western images may differ from nonwestern images, and so on.

IA. “The future” cannot be “predicted,” but “alternative futures” can, and should be “forecast.” Thus, one of the main tasks of futures studies is to identify and examine the major alternative futures that exist at any given time and place.

IB. “The future” cannot be “predicted,” but “preferred futures” can and should be envisioned, invented, implemented, continuously evaluated, revised, and re-envisioned. Thus the major task of futures studies is to facilitate individuals and groups in formulating, implementing, and re-envisioning their preferred futures.

1C. To be useful, futures studies needs to precede, and then be linked to strategic planning, and thence to administration.

The identification of the major alternative futures and the envisioning and creation of preferred futures then guides subsequent strategic planning activities, which in turn determine day-to-day decision-making by an organization’s administrators.

However, the process of alternative futures forecasting and preferred futures envisioning is continuously ongoing and changing. The purpose of any futures exercise is to create a guiding vision, not a “final solution” or a limiting blueprint. It is proper, especially in an environment of rapid technological, and hence social and environmental, change for visions of the futures change as new opportunities and problems present themselves.

II. Any useful idea about the futures should appear to be ridiculous.

IIA. Because new technologies permit new behaviors and values, challenging old beliefs and values which are based on prior technologies, much that will be characteristic of the futures is initially novel and challenging. It typically seems at first obscene, impossible, stupid, “science fiction”, ridiculous. And then it becomes familiar and eventually “normal.”

IIB. Thus, what is popularly, or even professionally, considered to be “the most likely future” is often one of the least likely futures.

IIC. If futurists expect to be useful, they should expect to be ridiculed and for their ideas initially to be rejected. Some of their ideas may deserve ridicule and rejection, but even their useful ideas about the futures may also be ridiculed.

IID. Thus, decision-makers, and the general public, if they wish useful information about the future, should expect it to be unconventional and often shocking, offensive, and seemingly ridiculous.

Futurists, however, have the additional burden of making the initially-ridiculous idea plausible and actionable by marshaling appropriate evidence and weaving alternative scenarios of its possible Developments.

III. “We shape our tools and thereafter our tools shape us.”

Understanding this statement by the Canadian futurist and philosopher of media, Marshall McLuhan provides the starting point of a useful theory of social change. Technological change is the basis of social and environmental change. Understanding how this works, in specific social contexts, is the key to understanding what can be understood of the varieties of alternative futures before us, and our options and limitations for our preferred futures.

Though technology is the basis, once certain values, processes, and institutions have been enabled by technologies, they begin to have a life of their own. Population size and distribution, environmental modifications, economic theories and behaviors, cultural beliefs and practices, political structures and decisions, and individual choices and actions all play significant roles in creating futures. However, our option in relation to these factors is best captured by the metaphor, “surfing the tsunamis of change.”

In addition, (1) the identification and analysis of long wave, cyclical forces and (2) the movement of “generations” through their life cycles (age-cohort analysis) are two other theories and methods useful in forecasting, envisioning, and creating the futures.

Basic Sources:

- Wendell Bell, Foundations of Futures Studies. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 1997. Two Volumes

- Jim Dator, Advancing Futures: Futures Studies in Higher Education. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger, 2002

- World Futures Studies Federation http://www.wfsf.org/

- World Future Society http://www.wfs.org/

- Institute for Alternative Futures http://www.altfutures.com/

- Hawaii Research Center for Futures Studies http://www.futures.hawaii.edu

Part 5 :: Obligations to Future Generations (practice)

Looking at Masdar through the lens of Dator’s readings.

Obligations to future generations and Jim Dator’s laws.

(1) Obligation to future generations.

(2) Dator’s three laws.

Download, make a copy and rename slides for in-class activity here.

Homework due before class Thursday:

(1) Finish Masdar in-class activity (Steps 11-14)

Part 6 :: Alternative Futures (Theory)

Dator: Exploring Different Alternative Futures Traditions

There is no such thing as “the future” out there that we are singularly headed towards; there are always multiple possible alternative images of futures. Although some images of futures are more likely than others, in times characterized by dynamic change, it is difficult to predict what will happen. For example, new technologies in the 18th century such as steam engines in the industrial revolution significantly changed how products were manufactured, transportation via trains, agriculture, the population in cities, and so forth.

Likewise, unforeseen events can dramatically change present realities; think of the impact of earthquakes, tsunamis, hurricanes, meteors, wars, tragedies, and so forth.

From a design perspective, one can prepare for alternative futures and be much better equipped to overcome challenges when and if they arise. In the following pages, we examine three different kinds of alternative futures at different levels: the organization, the nation, and a way to differentiate different kinds of images of futures.

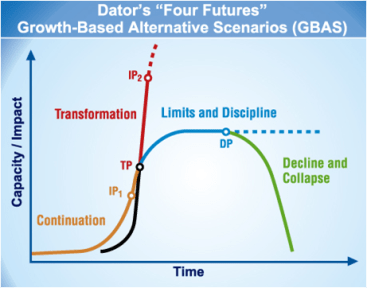

Generic Alternative Scenarios

Below are some excerpts from the article “Alternative Futures at the Manoa School”, Futurist Jim Dator describes how he struggled to make sense of the many conflicting images of the future and developed a way to cluster images of the future into four types. Read the text and answer the questions below.

The four generic futures

- Years ago, I, along with many other early futurists were trying to make sense of the many often conflicting images of the future that we encountered. Like many early futurists, I started out with a rather “scientific” and “positivistic” perspective, assuming that there was one, true future “out there” that proper use of good data and scientifically-based models would allow me to predict.

- I was soon disabused of that notion for many reasons. One pertinent here is the fact that I soon encountered many differing, often mutually-exclusive statements about how the future “would be”, all of which somehow made sense if one accepted their initial premises, data, and projections.

- Many of them were based on the assumption that society was moving from an “industrial society” to a “post-industrial society” with new technologies being a main reason for this change. These futures were often very positive. At the same time, there were equally convincing statements predicting a gloomy future based on concerns about overpopulation, energy and other resource exhaustion, and environmental pollution. Some statements ignored these issues entirely and were focused on space exploration and settlement, and there were also early optimistic studies of a fully automated world without work, perhaps with artificially-intelligent genetically engineered beings.

- In complete contrast were futures focusing on “human” and cultural matters such as poverty, human and animal rights, ethnicity, and gender. Some focused on globalization, others lauded local self-sufficiency. And so on.

- “Will the ‘real future’ please stand up?” I cried. Is it possible somehow to sort through these different images, rejecting false ones and reconciling differences among the true ones?

- I came to realize that there is no way to make an accurate prediction of “the future” of any but the most narrowly-and near term-focused entities. Futures studies is not about correctly predicting The Future. It is about understanding the varieties and sources of different images of the future, and of coming to see that futures studies does not study “the future”, but rather, among other things, studies “images of the future.”

- And so I turned my attention to collecting and analyzing as many images of the future as I could. I considered corporate and public long-range plans; statements about the future by politicians and the implication of laws and regulations; books and essays explicitly said to be about the future; the final paragraph in essays and the final chapter in books that often began, “and now, what about the future?” and proceeded to speculate. I analyzed images of the futures in science fiction in many modes, and statements about the future in public opinion polls, and, increasingly from my own students and from audiences I encountered worldwide.

- I considered many ways of organizing the thousands–millions–billions–of images, and examined the organizational schemes used by other futurists.

- But I eventually decided that all of the many images of the future that exist in the world can be grouped into one of four generic piles–four alternative futures. Sometimes the futures might seem to overlap between two or more piles, but most seemed to fall very naturally into one of the four–and no more (Note that I do except “flat” images of the future that once were dominant in societies experiencing essentially no or only slow social/environmental change, and the que sera, sera variety).

- These four futures are “generic” in the sense that varieties of specific images characteristic of them all share common theoretical, methodological and data bases which distinguish them from the bases of the other three futures, and yet each generic form has a myriad of specific variations reflective of their common basis.

- Also each of the alternatives has “good” and “bad” features. None should be considered as either a bad or a good future per se. There is no such thing as either a “best-case scenario” or a “worse-case scenario”. Also, there is no such thing as a “most likely scenario”. In the long run, all four generic forms have equal probabilities of happening, and thus all need to be considered in equal measure and sincerity. This last point is very important.

Assumptions underlying the four generic alternative futures

Rationale for alternative future one

“Continued growth” is the “official” view of the future of all modern governments, educational systems, and organizations. The purpose of government, education, and all aspects of life in the present and recent past, is to build a vibrant economy, and to develop the people, institutions, and technologies to keep the economy growing and changing, forever.

Thus, one alternative future is termed, generically, “Continued Growth” (often, “Continued Economic Growth”, or, if the economy is stagnating or declining, “Renewed Economic Growth”).

This is by far the most common of the four alternative futures since almost all official statements about the future are based on Continued Growth, and usually Continued Economic Growth.

Rationale for alternative future two

But some people are concerned about social and/or environmental collapse. The economy cannot–possibly should not–keep growing in our finite world (and especially not on a set of finite and fragile islands), they maintain. There may be many and different reasons that people fear (or hope for?) collapse: economic, environmental, resource, moral, ideological, or a failure of will or imagination. Or collapse may come “from the outside” by invasion from foreigners–or even outer space (meteors, for example). Hurricanes, tsunamis, earthquakes, a new ice age or rapid global warming, new and renewed pandemics–all of these are growing fears that might cause our fragile, over-extended, and heavily interconnected globalized world to collapse, either to the extinction of all humans, or else to a globalized New Dark Ages, some people feel.

So a second alternative future is “Collapse” from some cause or another (or their combination) and either to extinction or to a “lower” stage of “development” than it currently is. And while the examples given above are global, “collapse and extinction” is always a possible future for any community or organization. In fact, communities, organizations, and cultures vanish every day as economic and social forces render once-valuable institutions and places unneeded or unviable now.

It should be emphasized here that the “collapse” future is not and should not be portrayed as a “worse case scenario”. Many people welcome the end of the “economic rat-race” and yearn for a simpler lifestyle. Moreover, in every “disaster” there are “winners” as well as “losers”. One point of this entire exercise is to consider how to “succeed” in and enjoy whatever future you find yourself, by anticipating, preparing for, and moving affirmatively toward it. Consider how many people earn very good livings now as a consequence of the disasters of other peoples’ lives: lawyers, doctors, policemen, firemen, the military, and many more. None of these four futures is intended to be any better, or any worse, than any other. They are all “positive” to those who prefer them, and they should be presented positively.

I should also note that for most of my experience as a futurist, people have not wanted to consider “collapse” – especially for their organization or community. Even many futurists who use futures similar to the four here refrain from discussing collapse since most “clients” don’t want to consider it – though of course they should! But since the global economic collapse of 2008, and with the popularity of Diamond’s book, Collapse has almost become the new “official” view of the future for some people! They might be right.

Rationale for alternative future three

The third alternative future is labeled generically “Discipline”, or a “Disciplined Society”. It often arises when people feel that “continued economic growth” is either undesirable or unsustainable. Some people feel that precious places, processes, and values are threatened or destroyed by allowing continuous economic growth. They wish to preserve or restore these places, processes, or values that they feel are far more important to humans than is the acquisition of endlessly new things and/or the kind of labor and use of time that is required to produce and acquire them.

Others feel that while continued economic growth might be good, or at least necessary given the extent of poverty in the world today, continued economic growth is unsustainable because we live on a finite planet/island with rapidly depleting resources and a generally burgeoning population. Even though new technologies have enabled us to thrive beyond the “natural” sustainability of our resources, “continued growth” may be coming to a halt whether we like it or not as we run out of cheap and easily available energy resources and/or because of the choking contamination of our planet by the wastes of our industrial processes.

Thus, these people argue, we need to refocus our economy and society on survival and fair distribution, and not on continued economic growth. These same people may also say that we should orient our lives around a set of fundamental values – natural, spiritual, religious, political, or cultural – and find a deeper purpose in life than the pursuit of endless wealth and consumerism. Life should be “disciplined” around these fundamental values of (for various examples) “aloha”, “love of the land”, “Christian charity”, Ummah, Juche, or some other ideological/religious/cultural creed.

Rationale for alternative future four

The fourth alternative future focuses on the powerfully transforming power of technology – especially robotics and artificial intelligence, genetic engineering, nanotechnology, teleportation, space settlement, and the emergence of a “dream society” as the successor to the “information society”. This fourth future is called “Transformation”, or the “Transformational Society”, because it anticipates and welcomes the transformation of all life, including humanity from its present form into a new “posthuman” form, on an entirely artificial Earth, as part of the extension of intelligent life from Earth into the solar system and eventually beyond.

Part 7 :: Alternative Futures (applied)

- Generic Futures Jim Dator describes four different kinds of generic futures that cluster different types of images of futures. the other two kinds of alternative futures described above actually map to Dator’s generic futures.

-

- GROWTH A future that manifests the results of current trends and conditions extrapolated forward. This includes both positive and negative growth. Continued economic growth is the basis for the “official” view of the future held by most governments and organizations.

- DISCIPLINE A future in which a core guiding value or purpose is used to organize society and control behavior. For example, if continued economic growth inevitably leads to collapse, then mandating changes to the system and putting limitations on certain kinds of human behavior (discipline) is a proposed solution. China’s one-child policy is an example of a discipline solution to population growth.

- COLLAPSE A future in which major social systems are strained beyond the breaking point, causing system collapse and social disarray. Human organization returns to basic needs in order to rebuild. Global environmental collapse due to increased atmospheric and oceanic carbon dioxide levels is one example.

- TRANSFORMATION A fundamental reorganization of a society or system that signals a break from previous systems. The shift from nomadic hunter-gathering societies to stable, hierarchical agricultural societies was one of the most profound transformations in human history. Greater-than-human machine intelligence, and the revolution this would entail, is a popular transformation scenario.

- http://www.foresightguide.com/dator-four-futures/ (Links to an external site.)

Here is a representation of how some forces of change map to the four generic futures.

Futures Forces Growth Collapse Discipline Transform Population Increasing Declining Controlled Limited Energy Sufficient Scarce Limited Abundant Economy Dominant Survival Regulated Trivial Environment Conquered Overshot Sustainable Artificial Culture Dynamic Stable Focused Complex Technology Accelerating Limited Restricted Transformative Governance Corporate Local Strict Direct http://www.futures.hawaii.edu/publications/futures-theories-methods/DatorTISJFSRpt.pdf

Looking at Masdar City through the lens of generic futures

- Each teams work on each type of scenario (Growth, Discipline, Collapse, Transformation). Reorganize so that we have the following teams form larger teams e.g. the following teams are next to each other and have access to a wall/whiteboard to work on.

- Teams 1, 5 – Growth

- Teams 2, 6 – Discipline

- Teams 3, 7 – Collapse

- Teams 4, 8 – Transformation

12:20-13:15pm. Sensemaking of your alternative futures

Each team make a copy and rename the Google slides

Step 1. Represent the four alternative futures you made on Step 14 on a post-it note. Take a picture of the 4 post-it notes together. Upload the images to the slide deck.

Step 2. Sort and cluster the 16 alternative futures in your group. Use the walls and the whiteboard to do this. What features do the alternative futures have in common? Name each cluster. Document photographically and upload images to slide deck.

Step 3. Map your self-defined clusters from Step 2 to Dator’s four generic futures. What kinds of images of the future do your clusters fit under?

What futures forces seem most prominent in Masdar City Images of the Future clusters as described in each cluster?

Futures Forces Growth Collapse Discipline Transform Population Increasing Declining Controlled Limited Energy Sufficient Scarce Limited Abundant Economy Dominant Survival Regulated Trivial Environment Conquered Overshot Sustainable Artificial Culture Dynamic Stable Focused Complex Technology Accelerating Limited Restricted Transformative Governance Corporate Local Strict Direct

http://www.futures.hawaii.edu/publications/futures-theories-methods/DatorTISJFSRpt.pdf

Step 4. Each group has been assigned to one of Dator’s generic futures.

- Teams 1, 5 – Growth

- Teams 2, 6 – Discipline

- Teams 3, 7 – Collapse

- Teams 4, 8 – Transformation

How do your concepts from the Masdar assignment Step 6, and Step 10 map to the generic future your group is assigned to? It what way is it a match for the type of future and in what ways is it not a good fit?

Unless otherwise noted, this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Unported License.

Unless otherwise noted, this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Unported License.